A few years ago, we did a Child(ish) Reads on a book called Thirty Million Words by Dana Suskind, M.D. Its core concept is based on the research by Betty Hart and Todd Risley who, in 1995, found that by the age of three, children from higher-income families hear about 30 million more words than those from lower-income families. This disparity plays a substantial role in shaping academic outcomes and long-term success.

This topic has become top of mind this year as our school board is aligning its priorities with Georgia’s Early Literacy Legislation, which aims to ensure all children become proficient readers by the end of third grade. So why third grade?

By third grade, children transition from “learning to read” to “reading to learn.” If they haven’t mastered reading skills like decoding and comprehension by this stage, they’re at risk of falling behind in all subjects. Additionally, reading proficiency at this grade level is one of the strongest predictors of high school graduation and lifelong learning outcomes.

With my son now in the third grade, this hits a bit closer to home. While he enjoys math and science, reading has never really been his strong suit. He’s struggled with phonics and high-frequency words, and as the academic demands grow, those difficulties are becoming more evident. It got me thinking about how complex reading really is and what we can do to help our kids become confident readers who thrive in the future.

The Literal Brain

Reading is a cognitively demanding skill that involves a broad network of interconnected regions throughout the left hemisphere of the brain. When we read, the brain does the following:

- Visual recognition (occipital lobe and visual cortex) – identifies letters and words as visual symbols

- Letter word mapping (occipital-temporal region) – recognize familiar words quickly and automatically, allowing fluent readers to bypass sounding out each word

- Phonological mapping (parietal-temporal region) –breaks words into sounds known as phonemes (the smallest unit of sound that can distinguish one word from another) and matches letters to sounds to support decoding

- Morphological and syntactic analysis (frontal lobe) – helps determine word’s part of speech and its role within sentence structure

- Semantic integration (angular and supramarginal gyrus)– connects sounds and word forms to meaning, enabling coherent language

- Comprehension and meaning (temporal lobe and semantic cortex) – links written language to existing knowledge, memories, emotions, and ideas

- Speech and articulation (frontal lobe) – generates spoken words when reading aloud and supports internal speech during silent reading

- Fluency and automaticity (white matter pathways)– facilitates fast coordination across brain regions for fluent reading

The thing about reading is that it doesn’t come naturally. It’s a learned skill that takes teaching, practice, and lots of exposure. To help children become strong readers, schools often focus on two important tools—phonics and sight words.

Sights and Sounds

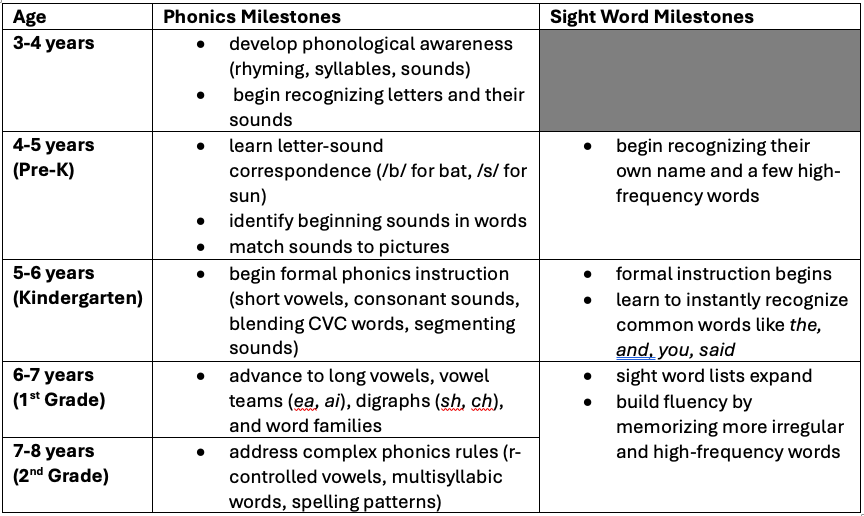

Phonics and sight words lay the groundwork for early literacy, each contributing uniquely to reading fluency. Phonics equips children with decoding skills, while sight words build a mental library of instantly recognizable terms. Together, they support a balanced approach to reading instruction.

By third grade, children are expected to have a strong foundation for fluent reading. But when that foundation is shaky, the signs are hard to miss. So what’s going on?

Lost in Translation

Reading challenges can stem from a mix of developmental, environmental, and instructional factors that can affect how the brain processes written language. No matter the cause, these challenges can erode a child’s confidence as a reader.

Common reading difficulties include:

- Dyslexia. This is a neurological reading disorder that affects a child’s ability to decode words, leading to difficulties in reading fluently. Although children with dyslexia have typical intelligence, they often find it hard to link letters with the sounds they represent. This can slow down their ability to read, recognize written words, and quickly name everyday items.

- Weak phonemic awareness. When children have trouble isolating and adjusting sounds in words, it can hinder both their ability to decode and spell accurately.

- Limited vocabulary. A limited vocabulary can delay comprehension and make it difficult to draw inferences from text. Children may substitute familiar words for less-known ones while reading (ex: replacing shouted with said).

- Poor reading comprehension. Challenges understanding or remembering written content, despite strong word recognition and decoding skills.

- Difficulties with attention. When kids have trouble staying focused while reading, they might mix up the order of words or lose track of what the sentence is really saying.

- Visual issues. When the eyes struggle to coordinate effectively, they may have trouble following words across a page, skipping lines, or unintentionally rereading the same sentence.

- Word-by-word reading. Limited reading fluency can lead to slow, laborious reading, with children needing to sound out each word individually.

- Misreading or skipping words. Sometimes kids mix up words that look alike, like saying clock instead of chalk. They might skip over little words like the or of, ignore punctuation, or even add extra sounds, turning both into broth.

- Limited exposure. When kids haven’t spent much time reading or being read to, it can reduce how quickly they pick up reading skills. To compensate, they might make up part of the story based on illustrations or context clues instead of reading the actual words on the page.

- Lack of motivation. When reading is perceived as unenjoyable, children may disengage from the task entirely, leading to avoidance and missed opportunities for skill development.

What to Do

It’s tough to see our kids struggle, but these challenges are more common than we think. Here are some ways to help them become better readers.

- Make it a routine. Consistency builds fluency. Dedicate at least 20 minutes each day to reading. Studies find that kids who read 20 minutes a day are exposed to 1.8 million words per year, a key factor linked to stronger academic outcomes.

- Read out loud. When kids are listening, they are also addressing reading. Reading aloud together not only fosters connection, but also models expression, rhythm and timing, and comprehension. Audiobooks can be a great addition too, offering rich language experiences wherever they go.

- Read whatever you want. Choice drives motivation, so let your child choose what they want to read: stories, facts, comics, poems, or even the dictionary. What matters most is that they feel successful and enjoy the experience.

- Model reading strategies. Kids learn through observation. Show them how you figure out tricky words by sounding them out, use clues from a sentence, or go back and reread to make sense of a story.

- Create the vibe. Environment shapes experience. A calm, welcoming reading space helps children concentrate and builds positive associations with reading, making it both meaningful and enjoyable

- Get a library card. Take regular trips to the local library and invite your child to discover books across a wide range of genres and topics. Let them follow their curiosity and choose stories that speak to their interests and suit their reading level.

- Practice phonics and sight words. Help build sound-letter relationships and word recognition with games, flashcards, and decodable books.

- Build vocabulary. Use vivid descriptions, play with rhymes, or try out tongue twisters. Games like Mad Libs spark creativity, and exploring new words together, whether in conversation or curiosity, all help build vocabulary in meaningful ways.

- Praise them like you should. As your child’s reading improves, don’t forget to celebrate the small wins, whether it’s sounding out a tough word or finishing a new book. Cheering for the little wins helps children stay motivated, feel proud of their progress, and grow a lasting love for reading.

If your child is still having trouble with reading, it’s a good idea to check in with their teacher. They may have noticed similar patterns and can offer valuable insight. Teachers and health care professionals are great partners as they can guide you through next steps to explore whether your child might have a reading disability. By sharing what you’re both seeing, you’ll build a clearer picture of your child’s needs and be better equipped to find the right support.

Like this post? Follow Child(ish) Advice on Facebook, Pinterest, Instagram, and TikTok.

Sources:

7 Most Common Reading Problems and How to Fix Them | How to Learn

What We Know About Reading and the Brain | Reading Rockets

One thought on “Book Smart: Kids and Reading”