The Book of Mothers by Carrie Mullins is pretty much the dissertation paper I’ve always wanted to write.

Millennial moms characteristically have done a lot of emotional work: reflecting back on their childhood trying to understand the context of how they were parented, and trying to figure out exactly what type of mom they want to be. A large percentage of our parenting is going to come from our own parents and experience, but TV, movies, books, and pop culture give us plenty of model moms to take note of.

So put on your AP Lit hat, and let’s get some close textual analysis.

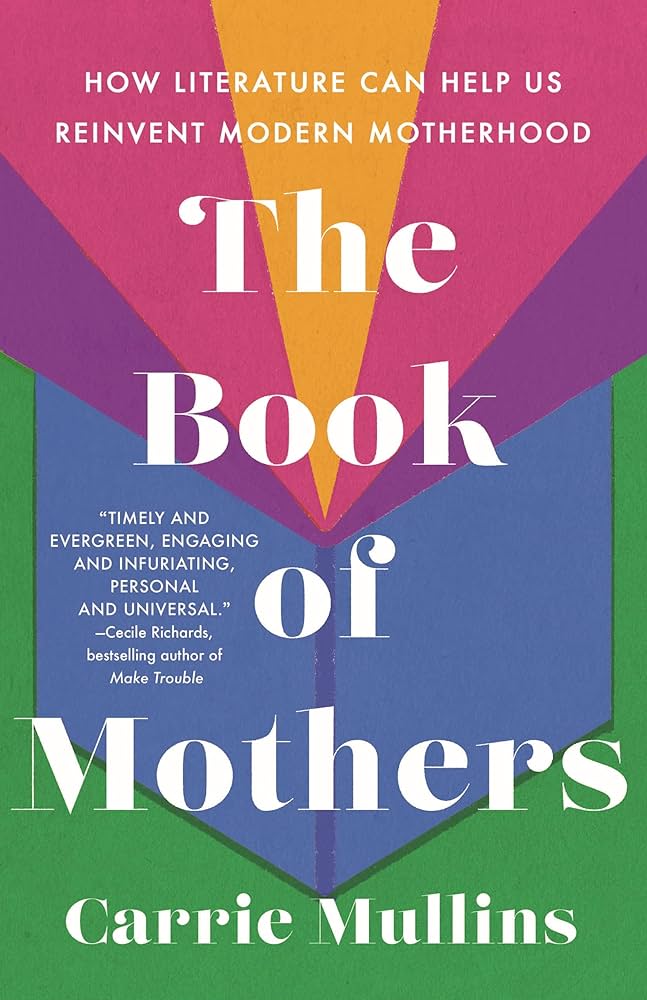

The Book of Mothers: How Literature Can Help Us Reinvent Modern Motherhood by Carrie Mullins

The Book of Mothers examines motherhood through 15 books of literature, starting from Mrs. Bennett “the original Real Housewife” to “Not my daughter, you b*tch” Molly Weasley.

“Our cultural understanding of motherhood has been built up over time, in a million places, and almost always by someone other than the mother herself…We need to differentiate between motherhood as the experience lived by the mother (which is empowering and beautiful and complicated) and motherhood as an institution (a construct made by men that keeps women, as Simone de Beauvoir put it, the second sex).”

In many of these books, the mother figure is not the main character. But through her, we can see motherhood in that time and context, as well as the author’s commentary based on their own mother-child relationship.

In addition, each mom paints a picture of the many stereotypes and superficial expectations of mothers of that period. Since this book is about Mom and not exactly how to parent, my takeaways are really more reflection points for you. Are moms in popular culture really just caricatures, or can they actually teach us lessons, showing how far women have come and informing the type of mom we want to be?

Women be shopping

Starting off light with the petty stereotypes: Moms only want to buy stuff, Moms are social climbers, Kids are accessories.

These chapters cover Mrs. Bennett, Emma Bovary, and Daisy Buchanan. Surface-level, do you really think these women were dedicated mothers concerned with the emotional well-being and nurturing of their children? No. They have other things to be worried about: social acceptance and debt collectors, not being penniless due to primogeniture, and hiding from a hit-and-run.

“The British writer Rachel Cusk has suggested we hate Emma Bovary because she is narcissistic, and narcissism is incompatible with motherhood: ‘Emma is the essence of the bad mother, the woman who persists in wanting to be the center of attention.’”

Are we giving these women a fair shake? Can mothers really be reduced to women who just buy stuff? Can the cool girl or the incessant matchmaker actually be a good mom? How much is an accurate portrayal of the time period, and how much is actual judgement?

Yeah, we know these questions are outlandish, but all over social media we see commentary about mothers and their spending habits, mothers outsourcing to nannies, etc. If you’re a SAHM, I’m sure you’ve gotten more than enough questions on what exactly do you do all day. And that’s crap! Especially coming off of Mother’s Day, I would hope that we mothers don’t have to continuously prove to other people that we do more than just cruise Target and be basic. And just because women do shop, have social lives and like to look nice, shouldn’t mean that they are negligent moms.

Mullins argues that if you spotlighted actual parenting on the Real Housewives, the show would be really boring. Motherhood humanizes women and that doesn’t make for good TV.

See: Any Real Housewives series, Peg Bundy, Mean Girls, Emily in A Simple Favor, Gone with the Wind, Big Little Lies.

Mom is angry

Marmee’s “I am angry nearly every day of my life” completely lands with Millennial Moms. Especially from Laura Dern in Little Women 2019, you can see how much mothers are pushing those feelings down to keep it together and stay regulated. Marmee is endlessly working and volunteering for her town. She keeps her girls safe and fed. She is the doer of good deeds, and keeps spirits up while her husband is a Civil War chaplain who cannot contribute anything financially.

“[Greta] Gerwig didn’t invent this scene; the lines are in the book and have been for one hundred fifty years. Why did it take us so long to notice?”

In The Handmaid’s Tale when pregnancies are valued much more than women themselves, we’re shown another type of anger that’s still omnipresent.

These two stories speak to the role of women on a larger scale and to their expectations within the home and for society. On one hand you have the mother that is the coordinator of the chaos, sacrificing herself for the good of her family and community. On the other hand you have women as a commodity; merely vessels for creating life.

So which is it? We’re either responsible for making this whole thing run, or are we only good for “the one thing a woman is supposed to do”. The latter especially hits hard for women who have struggled with infertility. Either way, it’s work that is historically undervalued by men and that makes us angry. What’s worse, being angry somehow translates to “we hate being moms” and that’s simply not true.

In my home and on this blog, we talk a lot about identifying and vocalizing feelings. We explain to our kids that yes, sometimes we get angry and it’s ok to feel that way. In the same vein, it is 100% ok for moms to be angry as well. I like to think that Marmee and Jo do find a way to process their anger instead of trying to find ways to not show or feel it. I also hope that for moms, we create environments, partnerships, and policies that value our labor.

See: The School for Good Mothers, Barbie, The Lost Daughter.

Women come last

Next, we have To the Lighthouse, Play It As It Lays, and Mrs. Bridge. I read To the Lighthouse by Virginia Woolf in high school and even then, Mrs. Ramsay came off as a busybody who served a husband that wanted all the praise. She wanted a perfect weekend and stayed in everyone’s business in order to get it. All of this effort and love goes unappreciated until her unexpected death in the second half of the book. Her husband and family finally realize how much she kept everything together, and *gasp* they actually miss her.

Virginia Woolf played with the archetype of The Angel in the House. The mother is responsible for the love, the children, the home; but at the end of the day, the father is still the Head, the enforcer, and she serves at his pleasure.

Do you really think Virginia was gonna put up with that?

“Woolf did not support her mother’s views, but she was still aware of what it cost to dismiss women like her mother, because dismissing women like her mother was what men had done for centuries…If women haven’t voiced their own experience, what, then, is authentic womanhood? How do we know it? What is ours, and what is man-made?”

These three novels portray mothers as subservient to their husbands. Even more so, they don’t have personalities, interests, or dreams of their own. So even when they are mothers and managing their households (choices they themselves made), they still have no real voice or sense of self.

“Twenty-five years after Virginia Woolf’s optimistic appraisal of her audience, an American wife [Betty Friedan, author of The Feminine Mystique] and mother of three sent out a questionnaire to her former college classmates from Smith. She inquired about their lives post-graduation and asked them to detail their ‘problems and satisfactions’ of the last fifteen years. She herself had a growing sense that there was something wrong with the way that American women were living their lives, but until she read the two hundred responses that flooded her mailbox, she wasn’t able to quite articulate that ‘schizophrenic split’ between the pervasive image of the happy homemaker and the feelings of boredom, depression, anxiety, and hopelessness shared by the women themselves.”

It’s more commonplace now that men and women are more equitable in their marriages. However, when kids come into the picture, you see a lot more discord when it comes to gender roles. How do you weigh tradition versus “modern parenting”?

Who makes more money still manages to trump the other duties that make a family work. This is further complicated by the economic inflation, the pandemic, and wage inequality. While there are pros for a traditional parenting/nuclear family arrangement, you can’t ignore a lot of the mental health issues that women had because of it.

“Friedan cites a Baruch study that aimed to find out why so many young wives were suffering from chronic fatigue. They discovered that the most tiring jobs are those that only partially occupy a worker’s attention while at the same time prevent them from concentrating on anything else. By the 1960s, this had become the exact kind of work involved in tending the home.

In one upper-income development where she interviewed, there were twenty-eight wives. Only one worked professionally. Sixteen out of the twenty-eight were in analysis or psychotherapy, eighteen were taking tranquilizers, several had tried suicide, and various others had been hospitalized for depression or vaguely diagnosed psychotic states.”

We can see now the consequences of what happens when women put themselves last. Let’s stop normalizing this self-sacrifice as honorable.

See: Betty Draper, June Cleaver, Revolutionary Road, The Giving Tree, Tully.

Moms are trying

“When parents share the down-and-dirty details of their experience, they help normalize difficult and previously ignored parts of childrearing. This is especially important for women, who need to talk about how hard it can be to breastfeed or how long sex hurts after giving birth or how exhausting it is being the default parent. The same principle extends to an infinite number of challenges that women face—no one is going to solve a problem we’re not talking about.”

It feels like a disservice to lump the other remaining books together: The Color Purple, Beloved, The Joy Luck Club, Harry Potter, Anne of Green Gables, Heartburn and Passing.

These books don’t go together in genre or time period. Their common thread: Moms trying.

In each of these titles, you have moms trying to figure out how to do this mothering thing, often times when they are financially insecure, or with children that are not biologically their own, or they’re in fraught marriages. Let’s not forget actual civil wars going on. There is real trauma on top of the job of being a parent.

Sometimes the moms are run down, described as dowdy, frantic and stressed. Contrast that with other mom characters. Those that are better styled and have more leisure time are then portrayed as less maternal, more strict and demanding mothers. Cause how can someone know if you are a good mother if you don’t look like an unkempt mess?

We’re all worried that if we make the wrong decision, our kid will be messed up for life. When you’re looking at narratives that put the responsibility of the child’s well-being squarely in the hands of the mother, it’s easy to see where the pressure comes from. By extension, the philosophy of the child’s success being a direct reflection of your parenting is just as harmful.

And despite the whole debate on what makes someone a good mother, we forget that ALL mothers will make mistakes no matter how hard we try day in and day out.

“It’s disturbing to think that one day my kids will look back at things I did and pick them apart for meaning, just as it terrifies me that something I did unconsciously might harm them forever. There’s a lot of shit going on! I want to plead with them now, so they remember it later, when they’re tempted to decide I ruined their lives.”

Even in the most privileged households, parenting is not easy. When society can get over the fallacy that parenting can be easy or that there is zero risk to it, then maybe we can start having real talk.

See: Bad Moms, Wild, Erin Brockovich, Room.

Moms are people, too

“’What will I say? What can I tell them about my mother? I don’t know anything. She was my mother.” I don’t know anything. She was my mother. These words perfectly capture the irony of motherhood. She was my mother is a phrase that can capture a singularly powerful love. But it can also be a shrug, a total dismissal of an individual.”

I am guilty of this for every gift-giving occasion. It’s so hard to find a gift for my mom. I resort to food gifts and gift cards, but truly I have no idea what my mom really likes besides playing Mahjong. Favorite shows, music, hobbies? No idea.

I hope that one day, my kids will know that I’m actually a fairly cool person. That I do a lot of cool stuff and have very discerning movie tastes. That my talents go beyond my parenting and even my profession. What parts of ourselves aren’t we sharing with our kids?

Our biggest parenting role, aside of the safety and health of our children, is being a role model. If we want our kids to be interesting and authentic, then we need to be interesting and authentic.

See: Any TGIF mom, Gilmore Girls, Morticia Addams.

I obviously love this book. It’s a contribution to the conversation about where our ideas of mothering come from. No two moms are alike generationally, and taking the long view of how we got here helps us navigate this role moving forward. We feel seen.

It’s especially poignant since we are the generation raised by TV. So whether we take our inspiration from books, plays, poems, or Carol Brady, we’re all piecing it together as we go along.

“Write stories about women, about mothers. Literature humanizes; it widens our perspective and has an unmatched ability to create empathy for characters unlike ourselves.”

Browse here for more Child(ish) Reads.

Follow Child(ish) Advice on Facebook, Pinterest, Instagram, and TikTok.